STUART JORDAN digs up the history of the first underground passenger railway.

STUART JORDAN digs up the history of the first underground passenger railway.

The Metropolitan Railway was built to serve commuters heading to the financial heart of the City of London. In this article I am going to look at the development and construction of the ‘Met’.

In the first half of the 19th Century, the growth of the City of London meant that the existing infrastructure couldn’t cope. An increasing population in London was commuting into The City, by cart, carriage, omnibus, or foot. This led to congestion on the roads, even before the motor car and the Congestion Charge were even imagined.

The problem occurred because, even though London was well served with railway termini, only Fenchurch Street was within The City itself. Passengers arriving at Euston, King’s Cross, Shoreditch, London Bridge, Waterloo, or Paddington had to continue their journeys using public transport or on foot. Even though this was a big problem, Parliament refused any new line or station to be built into The City.

went back to the

Charles Pearson and John Fowler; two men who were instrumental in getting the Met built.

In 1846, Charles Pearson, then Solicitor to the City, proposed a new station within the City of London that all railway companies could use. This was well before the forming of the ‘Big 4’, so each station and line was managed by different companies. Pearson was a strong supporter of the development of underground railways. Parliament refused his plans, so he went back to the drawing board. In 1852 the City Terminus Company was formed with the intention to build a railway from Farringdon (in The City) out to Kings Cross. This plan was supported by The City but failed to receive any interest from the railway companies themselves.

What then occurred was two years of wrangling to try and put together a cohesive plan that parliament would agree to. Eventually, the route was agreed – the line would be built from the Great Western Railway (GWR) terminus at Paddington to King’s Cross, where it would turn south to Farringdon and end at St Martin’s Le Grand. It would connect to the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) at Euston, and the Great Northern Railway (GNR) at King’s Cross. Permission to start construction was granted on 7th August 1854 by the North Metropolitan Railway Act.

Next came the task of raising the funds to pay for construction. It was estimated that around £1 million would be required to complete the project, just shy of £100 million in today’s money. Due to the ongoing Crimean War, backers were few and time extensions to the project were granted in 1856 and 1860. The GWR and GNR both pledged around £175,000 each, but spiralling costs meant that cuts had to be made to the route. The direct connection to Paddington was dropped, as was the line south of Farringdon to St Martin’s Le Grand. The City itself sold the Metropolitan £179,000 worth of land for £200,000 of shares in the company. With this transaction complete, the Met now had the funds required to start construction.

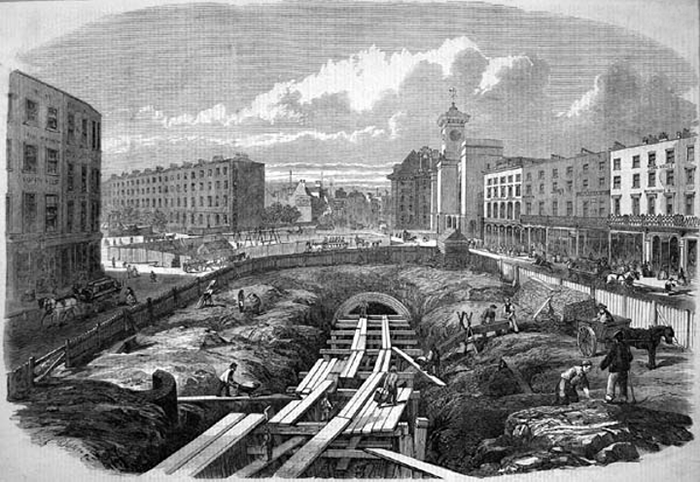

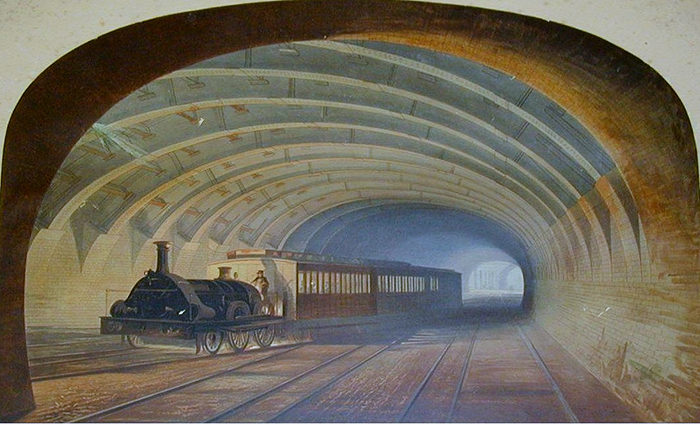

Cut-and-Cover tunnel construction near King's Cross.

The Metropolitan employed John Fowler as their chief engineer. Fowler had previously worked on the design for the Forth Bridge and was a prolific railway engineer. Construction on the Met line began in March 1860, mainly using a cut-and-cover method. A 33’ 6” wide trench was excavated for the route from Paddington to King’s Cross, down Marylebone Road and Euston Road. This was shored up by a brick retaining wall, and then covered with either a brick or iron girder arch before being covered over again. From King’s Cross, the line entered a 666m tunnel under Clerkenwell, which then followed the River Fleet Culvert to the station at Farringdon, near to the recently constructed Smithfield Meat Market. The tunnels contained double track which was set six feet apart. The track was dual gauge, allowing the running of both Standard Gauge and GWR Broad Gauge locomotives.

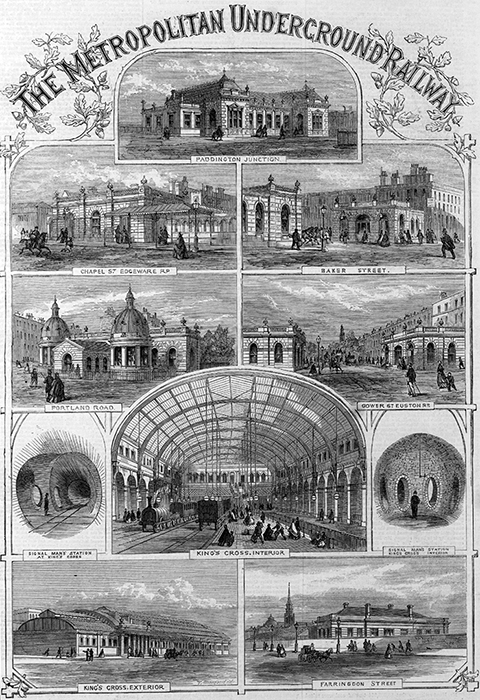

The London Illustrated News shows off the new stations.

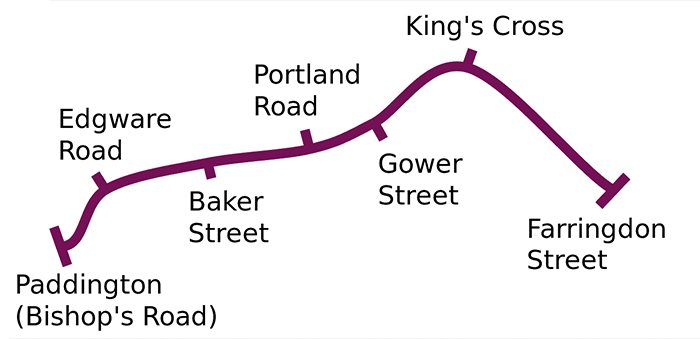

The route and stations built when the line was opened.

Testing was carried out on the line during construction from November 1861 onwards. Construction was completed in May 1862, with a final total expenditure of £1.3million. After inspections by the Board of Trade, the Metropolitan Line opened to the public on 10th January 1863. The line ran from Paddington to Farringdon Street via Edgware Road, Baker Street, Portland Road, Gower Street, and King’s Cross stations. 38,000 passengers used the Met on the first day and around 12 million passengers were being carried per year by 1864.

The Broad Gauge GWR Metropolitan Class.

The first locomotives used on the Met were the GWR Metropolitan Class. This Broad Gauge tank engine was built with a steam compressor to retain steam. Exhaust steam was directed back into the boiler via condensing pipes, rather than out of the chimney. However, soon after the railway opened, the Met and GWR had a falling out over the frequency of trains. GWR withdrew their locomotives from service in August 1863 and set them to run on other suburban routes. To cover the gap, GNR stock was used.

Beyer Peacock Metropolitan A Class Locomotive No.27.

The Met put a contract out to tender to provide a new class of locomotive, which was won by Beyer Peacock and in 1864, they provided eighteen Metropolitan Railway 'A' Class locomotives at a cost of £2,400 each. The 'A' Class was based on a design previously used on locomotives for the Tudela and Bilbao Railway in Spain and included condensing technology. They entered service burning coke to reduce emissions but later switched to smokeless Welsh coal. Twenty-one more 'A' Class were built by 1869 and twenty-four of a 'B' Class version with a shorter wheelbase also entered service between 1879 and 1885.

Beyer Peacock Metropolitan 'B' Class Locomotive No.59, with the front bogie the only obvious difference to the Class 'A'.

The world’s first underground passenger railway was now up and running, with the scene was now set for further expansion. In the next article, I’ll describe how the Met spread across London and how it would eventually create its own kind of suburb – Metro-land.